State UAS Drone Regulations

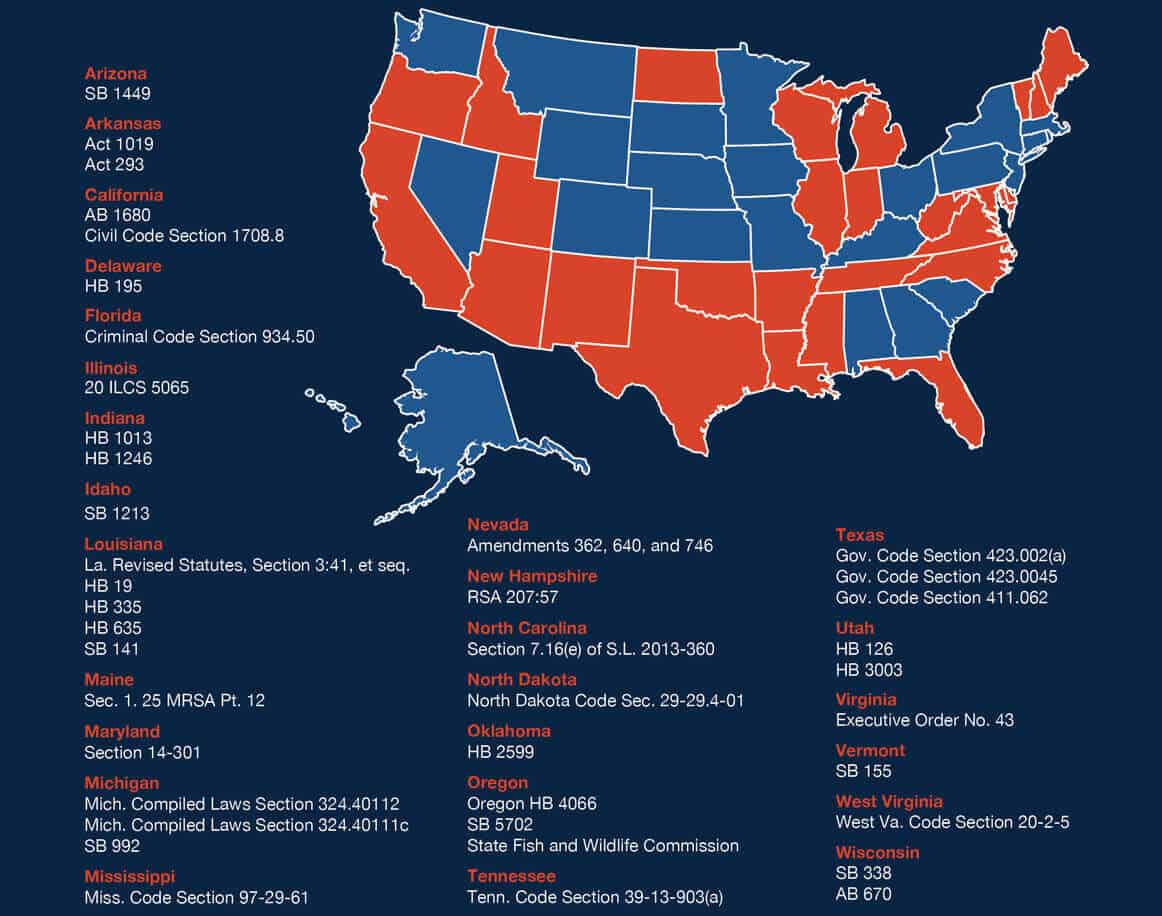

Individual states also have the ability to create their own regulations for drone flight safety and operations.

This list may be periodically updated however, please check with state and local governments on the laws in the area you intend to fly. Let's keep the airspace safe for everyone!

The overwhelming majority of state drone laws fall into three categories:

- Protecting the privacy of individuals

- Prohibiting drone use for hunting

- Limiting drone use by law enforcement

Other laws create drone commissions, restrict the use of drone in certain industries, or address common sense misuse such as flying over prisons or firework shows and outdoor venues such as concerts are often redundant to existing federal UAS drone guidelines.

DRONE LAWS: UAS DRONE REGULATIONS BY STATE

States are organized alphabetically, and each link will direct you to a separate page that highlights important drone law links for that particular state.

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

A

Alabama – AL

Alaska – AK

Arizona – AZ

Arkansas – AR

C

California – CA

Colorado – CO

Connecticut – CT

I

Idaho – ID

Illinois – IL

Indiana – IN

Iowa – IA

M

Maine – ME

Maryland – MD

Massachusetts – MA

Michigan – MI

Minnesota – MN

Mississippi – MS

Missouri – MO

Montana – MT

N

Nebraska – NE

Nevada – NV

New Hampshire – NH

New Jersey – NJ

New Mexico – NM

New York – NY

North Carolina – NC

North Dakota – ND

O

Ohio – OH

Oklahoma – OK

Oregon – OR

S

South Carolina – SC

South Dakota – SD

W

Washington – WA

West Virginia – WV

Wisconsin – WI

Wyoming – WY

At least 38 states considered legislation related to UAS in the 2017 legislative session. Eighteen states–Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina, Oregon, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Virginia and Wyoming–passed 24 pieces of legislation. Three states–Alaska, North Dakota and Utah–have adopted resolutions addressing UAS this year.

Alaska SCR 4 continues the Task Force on UAS and specifies additional membership and duties of the task force.

North Dakota SCR 4014 supports the development of the UAS industry in the state, congratulates the FAA on the first Beyond Visual Line of Sight Certificate of Authorization in the United States, and encourages further cooperation with the FAA to safely integrate UAS into the national airspace.

Utah's resolution, HCR 21, supports the building of a NASA drone testing facility and Command Control Center in Tooele County, Utah.

Colorado HB 1070 requires the center of excellence within the department of public safety to perform a study. The study must identify ways to integrate UAS within local and state government functions relating to firefighting, search and rescue, accident reconstruction, crime scene documentation, emergency management, and emergencies involving significant property loss, injury or death. The study must also consider privacy concerns, costs, and timeliness of deployment for each of these uses. The legislation also creates a pilot program, requiring the deployment of at least one team of UAS operators to a region of the state that has been designated as a fire hazard where they will be trained on the use of UAS for the above specifies functions.

Connecticut SB 975 prohibits municipalities from regulating UAS. It allows a municipality that is also a water company to enact ordinances that regulate or prohibit the use or operation of UAS over the municipality's public water supply and land.

Florida HB 1027 enacts the Unmanned Aircraft Systems Act. It defines critical infrastructure to include a number of energy installations and wireless communications facilities. The law generally preempts local regulation of UAS, but specifies that localities may enact ordinances relating to nuisances, voyeurism, harassment, reckless endangerment, property damage or other illegal acts. It also prohibits operation of UAS over or near critical infrastructure in most instances, making the offense a second degree misdemeanor, or a first degree misdemeanor if it is a second or subsequent offense. The law also prohibits the possession or operation of a weaponized UAS.

Georgia HB 481 defines unmanned aircraft systems and preempts localities from adopting UAS regulations after April 1, 2017. Allows regulation of the launch or landing of UAS on public property by the state or local government.

Indiana SB 299 defines unmanned aerial vehicle and creates a number of new criminal offenses. One offense, a “sex offender unmanned aerial vehicle offense,” occurs when a sex offender uses a UAV to follow, contact, or capture images or recordings of someone and the sex offender is subject to conditions that prohibit them from doing so. The offense of “public safety remote aerial interference” occurs when someone operated a UAV in a way that is intended to obstruct of interfere with a public safety official in the course of their duties. The law also creates the offense of “remote aerial harassment.” All of these offenses are class A misdemeanors. However, if the person has a prior conviction under the same section, it becomes a level 6 felony. It is also a class A misdemeanor to commit “remote aerial voyeurism.” It becomes a level 6 felony if the person publishes the images, makes them available on the internet or shares them with another person.

Kentucky HB 540 allows commercial airports to prepare unmanned aircraft facility maps. The bill specifies that UAS operators cannot operate, take off or land in areas designated by an airport’s map. It also prohibits operation of UAS in a reckless manner that creates a serious risk of physical injury or damage to property. Anyone who violates these provisions is guilty of a class A misdemeanor, or a class D felony if the violation causes a significant change of course or a serious disruption to the safe travel of an aircraft. The law specifies that these provisions do not apply to commercial operators in compliance with FAA regulations.

Louisiana SB 69 specifies that only the state may regulate UAS, preempting local regulation. The law also defines “unmanned aerial system” and “unmanned aircraft system.” It specifies that unmanned aircraft system does not apply to a UAS used by a local, state or federal government or other specified entities.

Minnesota SF 550 appropriates $348,000 to assess the use of UAS in natural resource monitoring of moose populations and changes in ecosystems.

Montana HB 644 prohibits using UAS to interfere with wildfire suppression efforts. Anyone who violates this prohibition is liable for the amount equivalent to the costs of this interference. The law also prohibits local governments from enacting an ordinance addressing the use of UAS in relation to a wildfire.

Nevada AB 11 adds transmission lines that are associated with the Colorado River Commission of Nevada to the definition of “critical facility” for the purpose of limiting where UAS can be operated.

New Jersey SB 3370 allows UAS operation that is consistent with federal law. The law specifies that owners or operators of critical infrastructure may apply to the FAA to prohibit or restrict operation of UAS near the critical infrastructure. Operating a UAS in a manner that endangers the life or property of another is a disorderly persons offense. It is a fourth degree crime if a person “knowingly or intentionally creates or maintains a condition which endangers the safety or security of a correctional facility by operating an unmanned aircraft system on the premises of or in close proximity to that facility.” Using a UAS to conduct surveillance of a correction facility is a third degree crime. It also makes it a criminal offense to operate a UAS in a way that interferes with a first responder actively engaged in response and to use a UAS to take wildlife. Operating a UAS under the influence of drugs or with a BAC of .08 percent is a disorderly persons offense. The law also applies the operation of UAS to limitations within restraining orders and specifies that convictions under the law are separate from other convictions such as harassment, stalking, and invasion of privacy. The bill preempts localities from regulating UAS in any way that is inconsistent with this legislation.

North Carolina HB 128 prohibits the operation of UAS within a certain distance of a correctional facility. Specifies that this restriction does not apply to certain people, including someone operating with written consent of the warden. It is a class H felony to use UAS to deliver a weapon to correctional facility, subject to a $1,500 fine. It is a class I felony to use UAS to deliver contraband, subject to a $1,000 fine. Any other violation of this section is a class 1 misdemeanor, subject to a $500 fine. HB 337 removes the exemption that specified that certain model aircraft were not unmanned aircraft. It allows the use of UAS for emergency management activities, including incident command, area reconnaissance, search and rescue, preliminary damage assessment, hazard risk management, and floodplain mapping. The bill makes other changes to align the state law with federal law. It also exempts model aircraft from training and permitting requirements for UAS.

Oregon HB 3047 modifies the law prohibiting UAS weaponization, making it a class C felony to fire a bullet or projectile from a weaponized UAS. It becomes a class B felony if serious physical injury is caused to another person. The law also creates an exceptions if the UAS is used to release a nonlethal projectile other than to injure or kill people or animals, if the UAS is used in compliance with specific authorization from the FAA, if notice is provided at least five days in advance to the state police and department of aviation, is reasonable notice is provided to the public regarding the time and location for the specified operation of the UAS, and if the operator maintains at least $1 million in insurance coverage for injury. UAS may be used by law enforcement to reconstruct an accident scene. The law also prohibits the use of UAS over private property in a manner that intentionally, knowingly or recklessly harasses of annoys the owner or occupant of the property. It specifies that this does not apply to law enforcement and a violation is a class B violation. It is a class A violation if it is a second conviction and a class B misdemeanor if it is a third or subsequent conviction.

South Dakota SB 22 exempts UAS that weigh less than 55 pounds from aircraft registration requirements. SB 80 defines “drone” as a powered aerial vehicle without a human operator that can fly autonomously or be piloted remotely. The law requires that UAS operation comply with all applicable FAA requirements. It also prohibits operation of drones over the grounds of correctional and military facilities, making such operation a class 1 misdemeanor. If a drone is used to deliver contraband or drugs to a correctional facility, the operator is guilty of a class 6 felony. The law also modifies the crime of unlawful surveillance to include intentional use of a drone to observe, photograph or record someone in a private place with a reasonable expectation of privacy and landing a drone on the property of an individual without that person’s consent. Unlawful surveillance is a class 1 misdemeanor. The unlawful surveillance provisions do not apply to individuals operating a drone for commercial or agricultural purposes or to emergency management workers using a drone in their duties.

Texas SB 840 permits telecommunications providers to use UAS to capture images. It also specifies that only law enforcement may use UAS to captures images of real property that is within 25 miles of the U.S. border for border security purposes. The law also allows a UAS to be used to capture images by an insurance company for certain insurance purposes, as long as the operator is authorized by the FAA. HB 1424 prohibits UAS operation over correctional and detention facilities. It also prohibits operation over a sports venue except in certain instances. The law defines “sports venue” as a location with a seating capacity of at least 30,000 people and that is used primarily for one or more professional or amateur sports or athletics events. An initial violation is a class B misdemeanor and subsequent violations are class A misdemeanors. HB 1643 adds structures used as part of telecommunications services, animal feeding operations, and a number of facilities related to oil and gas to the definition of critical infrastructure as it relates to UAS operation. Prohibits localities from regulating UAS except during special events and when the UAS is used by the locality. The legislation defines “special event.”

Utah HB 217 prohibits a person from intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly chasing, actively disturbing, or harming livestock through the use of UAS. Anyone who violates this law is guilty of a class B misdemeanor for the first offense and a class A misdemeanor for a subsequent offense or if livestock is seriously injured or killed or there is damage in excess of $1,000. SB 111 reorganizes existing laws addressing UAS. It also preempts local regulation of UAS and exempts UAS from aircraft registration in the state. The law addresses UAS use by law enforcement, allowing use for purposes unrelated to a criminal investigation. It also requires law enforcement create an official record when using UAS that provides information regarding the use of the drone and any data acquired. The law makes it a class B misdemeanor to fly a UAS that carries a weapon or has a weapon attached. Exceptions include if a person has authorization from the FAA, the state or federal government. The law also defines safe operation of unmanned aircraft, specifying operational requirements for recreational operators. The operator must maintain visual line of sight, cannot operate within certain airspace, cannot operate in a way that interferes with operations at an airport, heliport or seaplane base, cannot operate from specified locations, and must operate below 400 feet unless it is within 400 feet of a structure. Any operator who violates these requirements is liable for any damages and law enforcement shall issue a written warning for the first violation. A second violation is an infraction and any subsequent violations are class B misdemeanors. The offense of criminal trespass is modified to include drones entering and remaining unlawfully over property with specified intent. Depending on the intent, a violation is either a class B misdemeanor, a class A misdemeanor or an infraction. The law also specifies that a person is not guilty of what would otherwise be a privacy violation if the person is operating a UAS for legitimate commercial or education purposes consistent with FAA regulations. It also modifies the offense of voyeurism, a class B misdemeanor, to include the use of any type of technology, including UAS, to secretly record video of a person in certain instances.

Virginia HB 2350 makes it a Class 1 misdemeanor to use UAS to trespass upon the property of another for the purpose of secretly or furtively peeping, spying, or attempting to peep or spy into a dwelling or occupied building located on such property. SB 873 specifies that the fire chief or other officer in charge of a fire department has authority to maintain order at an emergency incident including the immediate airspace. Individuals who don’t obey the orders of the officer in charge are guilty of a class 4 misdemeanor.

Wyoming SF 170 defines the term operator and defines “unmanned aircraft” to exclude small unmanned aircraft, weighing under 55 pounds. The law requires the Wyoming Aeronautics Commission to develop rules regulating where unmanned aircraft can take off and land. The commission is also permitted to develop reasonable rules regulating the operation of unmanned aircraft through coordination with the unmanned aircraft industry and local governments. The law specifies that the commission does not have the power to regulate unmanned aircraft operation in navigable airspace. It also makes it unlawful to land an unmanned aircraft on the property of another person, but operators can pilot an unmanned aircraft over their own property.

Federal UAS Regulation

On June 21, 2016, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) released the first operational rules (PDF) for routine non-hobby use of small UAS. The new rule, which took effect in late August 2016, offers safety regulations for unmanned aircraft drones weighing less than 55 pounds that are conducting non-hobbyist operations.

The final rule requires drone pilots to keep an unmanned aircraft within visual line of sight and operations are only allowed during daylight and during twilight if the drone is equipped with “anti-collision lights.” The new regulation also establishes height and speed restrictions and other operational limits, such as prohibiting flights over unprotected people on the ground who aren’t directly participating in the UAS operation. There is a process through which users can apply to have some of these restrictions waived, while those users currently operating under section 333 exemptions (which allowed commercial use to take place prior to the new rule) are still able to operate based upon the conditions of their exemption. Further, the operator actually operating a drone must be at least 16 years old and have a remote pilot certificate with a small UAS rating, or be directly supervised by someone with such a certificate. To qualify for a remote pilot certificate, an individual must either pass an initial aeronautical knowledge test at an FAA-approved knowledge testing center or have an existing non-student Part 61 pilot certificate.

For more information on the rule, please review NCSL’s info alert.

On Dec. 14, 2015, the FAA unveiled an interim final rule for drone registration that would require consumers that own drones between .55 lbs and 55 lbs to register their crafts by Feb. 19, 2016. In May 2017, a federal court struck down the requirement for drone registration by hobbyists who operate their drone purely for recreation.

On Dec. 17, 2015, the FAA released a fact sheet on state and local regulation of UAS. The fact sheet includes examples of regulations that the FAA believes are within the authority of the states, including requirements for police to obtain a warrant prior to using a UAS for surveillance, specifying that UAS may not be used for voyeurism, prohibiting using UAS for hunting or fishing, or to interfere with or harass an individual who is hunting or fishing, and prohibiting attaching firearms or similar weapons to UAS.